News

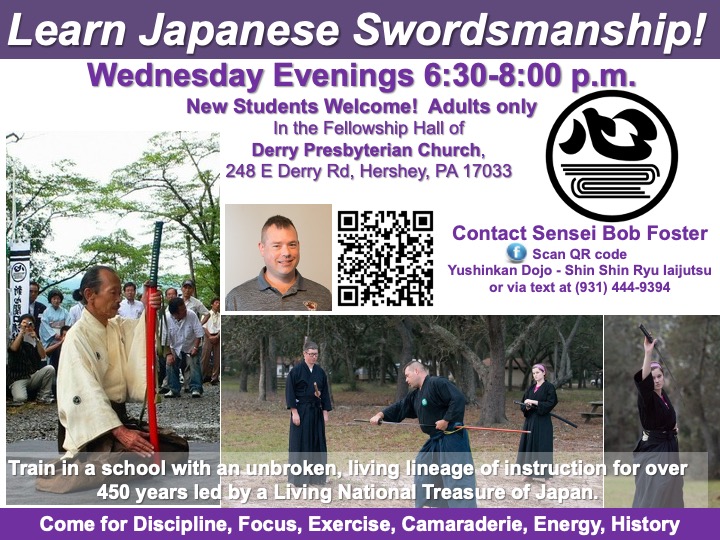

Learn Japanese Swordsmanship

July 19, 2023Derry member Bob Foster is offering classes in Japanese swordsmanship on Wednesday evenings in Fellowship Hall. Derry members may take lessons free of charge (excludes the cost of basic gear). To learn more, click here or text Bob at 931-444-9394.

Classroom Renovations Under Way

July 19, 2023Renovations are under way this week in Rooms 4 and 5 on the lower level. The wall between the two classrooms has been removed to create a large space for Tuesday evening programming, KIWI and other large group uses. The folding wall between rooms 7A and 7B will be removed and placed here so that Rooms 4 and 5 can also be stand-alone classrooms when needed.

Derry Church Grocery Bags Available Now

July 12, 2023Come and get your Derry Church reusable shopping bag on Sunday, July 16! The bags were created in a collaboration with the Communications & Technology Committee (CTC) and our Vacation Bible School leaders. All children who participated in VBS will take home their projects tonight in one of these sturdy Derry Church branded bags.

The CTC ordered plenty of extras so you can have one free of charge, to help promote Derry Church in the community as you do your shopping and errands. Bags will be available for pickup at the welcome table in the Narthex as long as supplies last. One per family, please.

Awesome VBS Volunteers!

July 12, 2023

Three cheers to this amazing group of volunteers who led Derry’s “A Place at the Table” Vacation Bible School this past week. Click to see photos from this fun and busy week.

This year’s Vacation Bible School explored how meaningful, healing, comforting and encouraging it can be to have “A Place at the Table.” Participating families donated to Derry’s mission partners that help everyone feel like they have “A Place at the Table.” Now church families are invited to support our mission partners by bringing items to worship on Sunday or dropping off at the church office by Thursday, July 20. Items needed:

Hershey Food Bank: Canned meats, soups, peanut butter, rice, shampoo, deodorant and toothpaste

Grantville Racetrack Ministry: Reusable water bottles

Gather the Spirit: Financial donations

Downtown Daily Bread: Men’s & women’s underwear, dark colored socks and disposable razors

Items may be placed on the chancel and financial donations may be placed in the secure donation boxes outside the kitchen and office suite. Mark your checks or envelopes “VBS Missions.”

Presbyterian Women Seek Volunteers for August Gathering at Derry Church

July 12, 20239 AM – 2 PM SATURDAY, AUG 19 AT DERRY CHURCH

Volunteers are needed to host the Gathering of Presbyterian Women in the Presbytery of Carlisle: a pianist for the morning session, ushers/people directors, and a clean-up crew, plus set-up helpers (1 pm Friday, Aug 18) and lunch prep & servers (10 am – 2 pm).

Contact Doris Feil to volunteer.

The afternoon program will be a presentation on Derry Church’s refugee resettlement experience.

Derry Dads Axe Throwing #2

July 12, 20237 PM TUESDAY, AUG 8 AT JOE OWSLEY’S HOME

Due to popular demand, the Derry Dads have scheduled another axe throwing event. All men welcome to attend.

Sign Up for the Corn Roast!

July 11, 20235:30 PM TUESDAY, AUG 15 AT MIKE & KAREN LEADER’S FARM, HUMMELSTOWN • RAIN DATE: AUG 17

This year’s corn roast features delicious corn on the cob roasted over hot coals, plus hot dogs and soft drinks. Please bring a side dish or dessert to share.

There’s a pond for fishing (bring your own gear) and plenty of activities and games for all ages to enjoy.

The corn roast is free. Your RSVP is required by Aug 8 to help the Leader family prepare for this large all-church event. Please fill out the form below to register.

If you’d like to make a donation to help offset the cost of the corn roast, you can do so at the event.

Need directions? Call the church office: 717-533-9667.

Many hands needed to set up and clean up: email Jess Delo to volunteer.

June 2023 Session Highlights

July 5, 2023- The Coordinating Council of the Presbytery of Carlisle recently drafted a new Purpose Statement and solicited comments on the statement from the various church sessions. As requested, Derry’s session reviewed and commented on the statement. Pastor Stephen will pass our comments to the Council.

- May’s financial reports show that year-to-date actual income continues to be ahead of expenses.

- Approved awarding a Brong Scholarship to Natalie Taylor for her final year at Messiah College.

- Stewardship & Finance requested that persons authorized to open a new Vanguard account be updated to Craig Kegerise, Pastor Stephen and Sandy Miceli. This authorization does NOT include access to the funds in the Vanguard accounts or ability to change any investment directives. The sole purpose is for the opening of a new account. The request was approved.

- The Health & Wellness Team requested approval to permit Derry member, Bob Foster, to use Fellowship Hall to conduct Shin Shin Ryu classes, a form of martial arts based on Japanese swordsmanship. The practice emphasizes presence of mind and calmness. There is no sparring or fencing. Participants utilize wooden and blunt swords to improve individual technique. The classes would be open to Derry members as well as community participants. The session approved the request subject to times and days that coordinate with the church calendar.

- Reviewed a Capital Procurement Request to fund landscaping work in the church cemetery. After restoring the cemetery (upgrading the walls, removing several trees, restoring the tombstones) there are high and low spots which need to be leveled and reseeded. The cost of the project is $10,937. Elders were asked to share the CPR with their respective committees, and the session will vote on the proposal at a future meeting.

- Approved Stewardship & Finance’s request to add Patrick and Lindsey Plassio as committee members. The Plassios, who recently joined Derry, live in Texas and will be joining the committee meetings via Zoom. We are happy to welcome their participation.

- The Personnel Committee brought three matters before the session which were approved:

- After conducting a review of M.E. Steelman’s performance six months into her new position, the committee recommended increasing her salary to $50,000 (an increase of $4,000).

- Sue George submitted a request for a 20-day sabbatical in April 2024 to coincide with the 300th anniversary trip to Ireland and Scotland. During that time, she will be photographing the sites and gaining a deeper understanding of Derry’s past. Sue plans to document the experience with pictures, stories, and reflections in a format that those who are not on the trip can easily access.

- As Pastor Stephen, Sue George and Kathy Yingst will be participating in the 300th anniversary trip in 2024, Debbie Hough will be contracted to assist with office coverage while they are away.

LOOKING GOOD: 2023 Mission Houses

July 5, 2023Last month Derry’s mission team in the Dominican Republic helped to build these two houses along with a crew from Morgan Stanley NYC. Here they are with fresh coats of paint, all ready for sheltering their new owners.

ELIZABETHTOWN’S TINY ART WAK FEATURES DERRY’S OWN ELIZABETH GAWRON

July 5, 20234-6 PM SATURDAY, JULY 8 ON MARKET STREET, ELIZABETHTOWN

Derry member and artist Elizabeth Gawron is one of the many local artists who will be creating works and demonstrating techniques along Market Street for Elizabethtown’s Tiny Art Walk. Stop by and say hello!

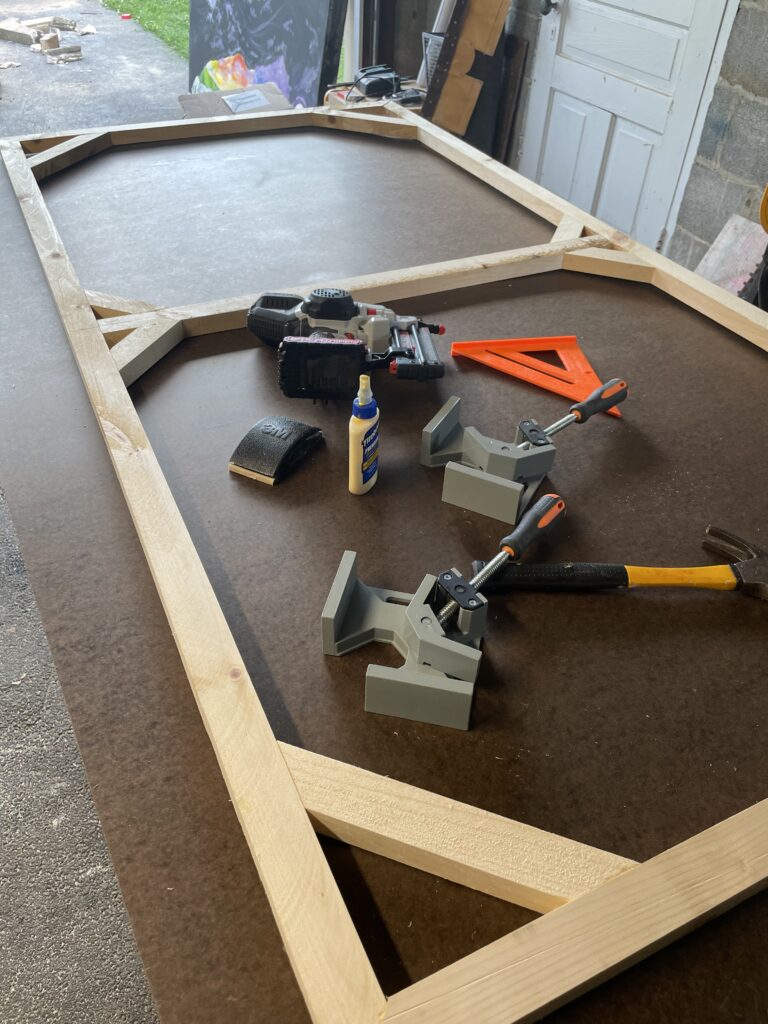

FIRST LOOK: ART INSTALLATION PROGRESS

July 5, 2023Derry member Luke Gawron has started on the art installation to be placed in the Narthex by the end of the year. He measured and cut a 7′ x 3′ piece of masonite, then primed it so it’s ready to be painted with images of Derry Church life. Learn more about Luke’s project in this short video.

New Member Classes Begin Aug 6

June 28, 20239:15 AM SUNDAYS, AUG 6-13-20 & 27 IN THE JOHN ELDER CLASSROOM

The summer series of New Member Discovery Classes gives you the opportunity to learn more about the mission and ministry of Derry Church, and discover how you’d like to share your talents in the life of the church. You’ll also meet staff and leaders over the course of four weeks and tour the church. Those who decide to join will be received on Sunday, Aug 27.

Registration is appreciated by not required: sign up online or call the church office (717-533-9667).