News

Organ Recital Features Helen Anthony

May 3, 20233 PM SUNDAY, JUNE 11 AT MESSIAH LUTHERAN CHURCH, 901 N. 6TH ST, HARRISBURG

Helen Anthony, Director of Music & Organist at Messiah Lutheran Church, will present organ works by J.S. Bach.

Helen is a 1976 graduate of Westminster Choir College, and completed graduate level course work at West Chester University. She has held church positions in the Harrisburg, Hummelstown, Hershey areas. Helen retired from Derry Church in 2015.

Proceeds of this benefit concert will support restoration of the church’s Moller Organ comprised of three manuals and 33 ranks. General admission tickets are $30 and are 100% tax deductible.

There are also sponsorship opportunities available at the following levels:

- JS Bach $1,500

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart $1.000

- Ludwig Van Beethoven $500

- Frederic Chopin $250

- Friends of Messiah any amount

The recital will last one hour, with a reception following in the social hall. Your support of this inaugural concert insures that future generations will enjoy the organ in worship services praising God.

Love INC’s 3rd Annual #RUNYOURRACE 5K Run/Walk and 1M fun Run

May 3, 20238 AM SATURDAY, JUNE 24 AT SPRING CREEK CHURCH OF THE BRETHREN, 335 EAST AREBA AVE, HERSHEY • REGISTER NOW

Last year over 140 runners and 11 sponsors joined together to raise over $8,400 for the programs of Love INC of Greater Hershey. We are looking forward to another successful event this year and would love for you to join us. The course includes the scenic Milton Hershey School campus.

Cost: $30/Adult and $20/Student by June 5th ($5 increase after 6/5)

Birthday Offering Update #3

May 3, 2023The Birthday Offering of Presbyterian Women celebrates our history of generous giving. Launched in 1922, the Birthday Offering has become an annual tradition. It has funded over 200 major mission projects that continue to impact people in the United States and around the world. While projects and donation amounts have changed over the years, Presbyterian Women’s commitment to improving the lives of women and children has not changed.

The second project for 2023 is Berhane Yesus Elementary School Kindergarten Construction in Dembi Dollo, Ethiopia. Located in the western highlands of Ethiopia, Berhane Yesus Elementary School seeks to change lives by sharing the “Light of Jesus” and by providing the best possible educational experience for children of Dembi Dollo. Berhane Yesus provides children the possibility of a better future by preparing them for the rigorous high school education and a life of Christian service.

The school is the first entry point to education for children of subsistence farmers, migrant workers and displaced groups of people. This K-8 school has been serving the community and been a part of the Presbyterian Church in this rural community since 1921. A kindergarten class was added to the school in 2012, but with no available space for class, the children met in the chapel. Over the years the number of kindergarten students has increased and now a space of their own is not only needed but required by the government to be able to remain open. Western Wollega Bethel Synod provide land for the classroom and the Birthday Offering grant will provide all necessary funding for construction.

Your continued support will allow PW to fund next year’s projects. You can give online, deposit checks in the offering boxes, or mail checks to the church notated “PW Birthday Offering.” Together let us lovingly plant and tend seeds of promise so that programs and ministries can grow and flourish.

April 2023 Financial Snapshot

April 26, 2023Cash Flow – Operating Fund as of 3/31/23:

| ACTUAL | BUDGETED | |

| Income YTD: | $379,138 | $324,750 |

| Expenses YTD: | 333,500 | 342,720 |

| Surplus/(Deficit) YTD: | 45,638 | 36,418 |

Postponed: Local Mission Opportunity

April 26, 2023The work project scheduled for Saturday, April 29 in Grantville has been postponed until further notice while we await issuance of a building permit. We’ll let you know when it is rescheduled and check your availability at that time. Thanks for volunteering!

Last Minute Info: Lasses & Lassies Banquet

April 26, 2023- Your last chance to purchase tickets for the Lasses & Lassies Banquet is Sunday, Apr 30! The bridal show consists of dresses worn in the past, not ones to buy now.

- Men are needed to serve and clean up for the banquet on Sunday evening, May 6. Dinner for the volunteers will be provided at no cost. Contact Doris Feil by Sunday, Apr 30.

Birthday Offering Update #2

April 26, 2023The Birthday Offering of Presbyterian Women celebrates our history of generous giving. Launched in 1922, the Birthday Offering has become an annual tradition. It has funded over 200 major mission projects that continue to impact people in the United States and around the world. While projects and donation amounts have changed over the years, Presbyterian Women’s commitment to improving the lives of women and children has not changed.

The first project for this year is Making Miracles Group Home Phase II in Tallahassee, Florida. This home helps young mothers break the cycle of abusive relationships, addiction, incarceration and early motherhood – a repeating pattern that is difficult to break and overcome. Since it’s inception in 2010, Making Miracles has served over 100 women and their children by providing a one-year live-in program designed to support young mothers and help them develop skills to live independently and care for their children.

Current eligibility criteria require residents to be pregnant and/or have a single child up to the age of three, but mothers who have a single child older than three or multiple children often seek help. With this Birthday offering grant they will purchase a second group home to serve an additional five families who are at risk of experiencing homelessness. With loving support and tools to establish stable, permanent housing, these families can look forward to a hopeful and successful future.

Your continued support will allow PW to fund next year’s projects. You can give online, deposit checks in the offering boxes, or mail checks to the church notated “PW Birthday Offering.” Together let us lovingly plant and tend seeds of promise so that programs and ministries can grow and flourish.

Travel Notes from Pastor Stephen: It’s a Sad Song

April 22, 2023

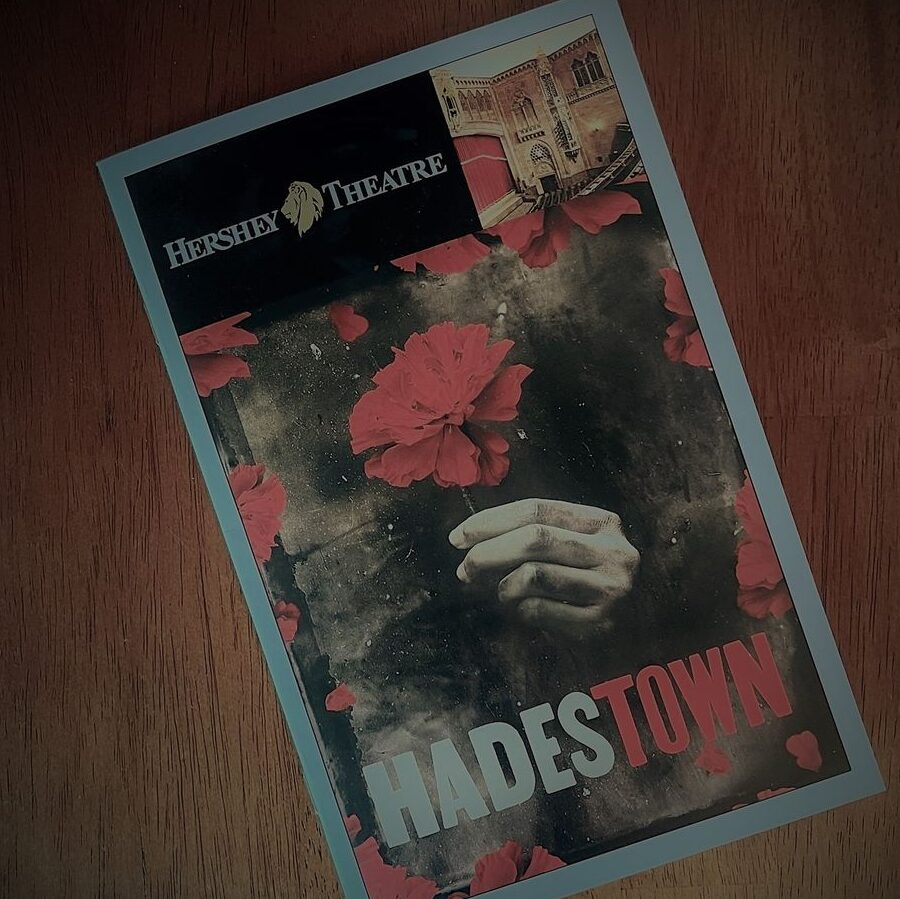

Almost three weeks ago, Courtney and I went to see Hadestown at the Hershey Theatre. It’s a musical based on the Greek tragedy of Orpheus and Eurydice. It being a Greek Tragedy, there is no happy ending. The cast of Hadestown, especially the narrator Hermes, warns the audience repeatedly that “it’s a sad song.” And yet, if you are not familiar with the tragic story, the ending can catch you off guard. Courtney even admitted kind of hoping they would change the ending. We long for happy endings, don’t we? We prefer it. Authors are lambasted when their characters don’t find lasting joy, when everything doesn’t end in the predictable perfect way of a Hallmark Christmas movie.

Hermes sings a final song that speaks a powerful truth that has been with me since first hearing it: “It’s a sad song. It’s a sad tale, it’s a tragedy. It’s a sad song. But we sing it anyway.”

History is often a sad song. The album of history is replete with tragedies and atrocities and heartbreaking ballads, but we sing them anyway. We have to. We know how it ends and yet we must sing it again and again. We owe it to those whose song it is, whose cries created the melodies, whose pain penned the verses.

We cannot just skip past the songs and play the top hits on repeat over and over again as if those were the only songs ever sung.

That is how we often want to treat history. We were talking with Susan Neiman last night about how much we didn’t learn of history in school. I never heard the name Emmitt Till until I was in Seminary. I never learned much of the time between the civil war and reconstruction. The only way I’ve come to know the worst of our history is through my own initiative and research. We wonder: do we really need to know these things?

We argue with it and ourselves, rationalizing why we shouldn’t have to lift up the darker moments. Why do we have to confront this, and hear this story? Why should we be forced to feel sadness or shame? We weren’t there! We didn’t do this! But we are here and someone in the not-so-distant future may feel the same about what we are currently doing and allowing to be done. Our time and our song will not be a purely happy and triumphant one. Let’s not kid ourselves. Future generations will not want to sing of the deadly school shootings, but they will need to. They will not want to hear the song of racial injustice that has continued to play in this country even as we have tried to ignore it.

History is a sad song, but we sing it anyway.

Prominent German philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel said, “We learn from history that we do not learn from history.” How are we to learn from a history we cannot change, and not, as Hegel warned, to miss its lessons? We confront it, we learn it, we sing it again and again. We can’t just bury the song and pretend it was never sung at all.

After WWII, East and West Germany took opposite approaches to reckoning with the past. The problem was complex, as every institution in the country — from the local governments, to schools, to art museums, police forces, hospitals, and of course the national government — was stained from Nazism. As much as some wanted justice done, it was also logistically impossible to prosecute every citizen. While some notorious Nazis faced trials and justice, many escaped and many flew under the radar. West Germany ended up choosing a policy of democratizing the institutions and reintegrating former Nazis, with the hope of rehabilitation and reconciliation over time. This had mixed success and also posed many problems. It’s hard to have reconciliation without justice, and many felt too many perpetrators of the horrors of WWII escaped justice. The US brought many former Nazi scientists and engineers to the US to work on American military projects to help defeat the Soviets.

East Germany, on the other hand, adopted a policy of denial of the mere existence of former Nazis in its population. Their line was that all the Nazis were in the West and they had to protect ourselves from their stain, so they built a wall. East Germany imposed (or had imposed on them) a new, Communist dictatorship that shamed the people for their past sins and claimed the moral high ground in opposition to the West. The first concentration camp memorial was created by East Germany, but it was more to remember the communist victims and not the Jews. In fact, the words “Jew” and “Jewish” were never uttered at the opening ceremony.

Both approaches had their successes and their problems, but ultimately, it was Western leader Willy Brandt, and not Eastern leader Walter Ulbricht, who knelt at the Warsaw Ghetto memorial and openly acknowledged Germany’s complicity in the murder of millions. It was the West the first confessed and confronted its past, and began to sing the sad song.

Bryan Stevenson, founder and director the Equal Justice Initiative, said the country cannot heal until it confronts the truth of what happened, especially in the South.

“This landscape is littered with a kind of glorious story about our ‘romantic past,’” said Stevenson, a lawyer who has helped overturn the convictions of more than 125 wrongly condemned prisoners on death row. “You can’t say that if you fully understand the depravity of human slavery, of bondage, of humiliation and rape and torture and lynchings of people.”

I wrote a few days ago about my need to visit the new National Memorial for Peace and Justice. It’s not because it will be such an enjoyable trip. Honestly, I have no desire to go to Alabama, but I need to go. I need to hear the song. I need to read the names, those whose song it is. The reality that happened is shameful but and I feel shame it happened, but I don’t feel (or need to feel) personal guilt. I can’t help but wonder why the song has been silenced for so long. Is it because of shame or guilt or the fear of that? I don’t know. I do know I never learned about the history of lynching in school. Why do you think that is? What story are we trying to tell about our nation and why?

We were talking with Susan Neiman over dinner last night and shared how some of the youth of our church have never heard about the history of lynching in the US. That’s not by accident. We want to control the narrative of history and present a sanitized version, the best of hits of our nation. There’s a right and wrong way to present the material, of course, and trying to make students feel personal guilt and shame for what happened 75-100 years ago is not the way to do it. But there are correct and helpful ways to let students investigate the hard history that our lives are built upon whether we acknowledge it or not.

In an adjacent garden at the Memorial for Peace and Justice lie 801 steel monuments identical to those hanging in the memorial. These replica monuments await representatives from counties where the lynchings occurred to claim them, take them back home and display them as a testimony to what happened, and efforts at truth and reconciliation. But most remain unclaimed because we don’t want to remember. We don’t want the song playing in our town. It’s a sad song we don’t want to sing because of shame or fear or guilt or simply because we want to pretend our history is only a triumphant and glorious song deserved to be sung by all the world.

Have we confronted our past of slavery, and Jim Crow, and the treatment of Indigenous people among other sad songs? Have we learned their lessons? Looking at our country today, I can’t say we have. Not really.

With that said, we also cannot make a study of history only a study in shame and guilt. That is also not helpful. If we treat one group of people as monsters and tell them they were and are monsters, guess what they will become? Monsters. We also can’t solely identify ourselves by how some narrow subset we could be identified with acted in history. We cannot define ourselves as forever the perpetrators of forever the victims. That has been the case to some degree in Germany. Germany has done some good reckoning with history work, but at times it can go too far. We talked about this with Susan Neiman last night. She made the point that Germans now are afraid to ever give critique to the nation of Israel. Germany has done a good job naming the evil done in the past and owning up to the fact that the German people were perpetrators of great violence and evil, but that’s not all they are. Unfortunately, the scale is tipping so that some Germans are forever the perpetrators and Jews are forever the victims. The same is happening to a degree in the US with white people identified as perpetrators and black people as victims. That is not a helpful way to engage with the history or the present for either group. There’s a whole lot more to say about that and consider that I hope to reflect on soon. Susan Neiman suggested a few books to read which I will do including Woke Racism by John McWhorter.

We need to be able to sing the sad songs, but in the same way we shouldn’t ignore those we shouldn’t fail to sing the hopeful ones and the songs of heroes and triumph. We are not only our worst moments and we are not solely defined by our best.

I’ve appreciated this time in Germany. I’m by no means an expert on the rise and fall of the Third Reich in Germany or the oppression faced by Jewish and other victims of the Holocaust, but I know I need to learn the lessons from this sad and abhorrent time in our collective history.

The lessons of the Holocaust are many, and though there is always more to learn, we somehow understand the most important one: we must never get to that place again. It remains me of what I heard in Northern Ireland again and again: “We cannot ever go back to how it was. We aren’t sure how to best live together but we know we need to do it better.”

We talk about how the whole human race is a family: we are brothers and sisters. Yes, I believe that’s true, but in acknowledging that we also need to remember that one of the earliest stories we have about siblings, Cain and Abel, is also the story of the first murder. Biblical families have a lot of sad songs: rape, incest, murder, robbery, division. The oldest family stories repeat throughout history: Cambodia, Rwanda, Burma, China, Armenia, the Soviet Union, Ukraine, and yes the US. We are no exception, our hands and our histories are not clean. No passive solution will suffice to overcome the kind of inhumanity we can enact on each other. So, where do we begin?

First: we must refuse to live by lies, especially with our use of words.

I value the First Amendment of the US Constitution: the freedom of speech (and also the freedom to read). It always concerns me when books or people are banned from public education, discussion, and debate. While not every book or person is developmentally and curricula appropriate for different levels of education, access to easily engage them should not be hindered.

The freedoms to speak and read are so important because, messy as it often is, it is by speaking and reading that we learn how to think. Often, we either change or confirm what we believe because we hear something coming out of our own mouths. I process my own thoughts best by discussion with others. I need good, trustworthy friends I can work stuff out with who won’t judge me when I say something that’s not perfectly articulated. Sadly, we are at that point. People are afraid to speak for fear of being shamed and cancelled. We have to be careful with words, yes, but we also need spaces to freely explore our own thoughts with our own voices. It’s by speaking and thinking, reading and writing that we understand the nature of reality itself. And we need to speak and think, read and write, more than ever, precisely because we are in a crisis of reality. What is true? Who are we? What is our purpose? These are questions humans have always wrestled with and we will continue to wrestle with them now especially after so many world altering events in such a short span of time.

As a follower of the philosopher Georg Hegel, Karl Marx believed in history as a moral force, moving purposefully and inevitably toward a utopian end. It reminds me a bit of Martin Luther King Jr’s famous quote, “the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.” Hegel and Marx are big in Berlin and we visited statues of both of them.

Hegel’s predecessor, Immanuel Kant, had rejected the Greek-Jewish-Christian notion of a knowable reality (logos) for a belief that nothing is knowable, and that reality can only be criticized, and deconstructed, to achieve a moral end. This is not just a philosophy about history, but a theory about the nature of reality itself and what we can know (epistemology). Marx knew that to actualize the goal of Communism would require a total reinvention of society, or as he put it: “[the] ends can be attained only by the forcible overthrow of all existing social conditions.” (Basically the burn it all down and start again model.)

In 1917, the Bolsheviks in Russia took him up on the challenge, and many nations have followed suit, including the German Democratic Republic (East Germany) in 1949. It wasn’t possible for Marx to know the real-world outcomes of the theory he and Friedrich Engels had helped to codify. Nothing like the Communism they proposed had ever existed before, nor had the kind of total dictatorship it necessitated: the repression of individual rights, the confiscation of private property, and the silencing of all dissent by eliminating the right to free speech. (The communal living in the Book of Acts for example is nothing like a Communist political and economic system though sometimes it is wrongly lifted up as such.

In the end, the Communist experiment cost the lives of at least 100 million people across several countries, including the starvation of four million Ukrainians in the state-instituted famine called the Holodomor. That famine reminds me a lot of the great hunger (or potato famine) in Ireland that was caused in large part by the British Empire. While there was a potato blight, there was still plenty of food; the Irish just didn’t get it.

There is a current trend and desire from people on the left and right to place limits on the freedom to speak openly, at risk of giving offense. It’s extremely cynical and audacious to assume that the main reason our fellow citizens might want to speak freely is to cause harm to others. Yes, offense can be made in that process, sometimes by accident, by ignorance, or even on purpose. But we also need to grow a bit thicker skin, too.

The vast majority of those who wish to assert their right to speak are doing it for a variety of justifiable reasons (even if we completely disagree), ranging from the basic right to live their daily lives, find better lives, deal with pain and suffering, and explore what it means to be human, to the real need and responsibility to hold our governments and institutions to account for past and present actions.

Millions across the world have considered this a right worth dying for. Over the last several years, our world has been hit by wave after wave of crisis from disease, natural disasters, war, racial unrest, and rancorous political division. Opportunists have seized upon these moments of turmoil, unrest, and fear with ready-made solutions to vastly complicated and nuanced problems. It was this sort of landscape that made someone like Hitler both possible and popular.

We have seen what lives inside of our neighbors when fear is introduced into the mix. Fear is a powerful motivator. I’ve always said when politicians appeal to fear and greed, they are manipulating us for a purpose that usually has nothing to do with the fear and greed they are peddling. Fear was behind the Nazi regime and the Communist regime that Germany lived under in the last century. Fear is what leads to concentration camps and gulags, as well as the internment camps, vast prison systems, lynchings, and eradication of native populations that have existed and sometimes persisted in our own country.

We need to pay close attention to the opportunists and to the ones peddling fear and greed, shame and guilt, especially if that’s the only currency they trade in. Notice who is telling you what the biggest threats are to your way of life and freedom and why. Notice who is telling you how outraged you should feel and who should be cancelled. Notice who is eager to control others’ behavior or words or public image. Influencers, and sadly elected leaders of both parties, provoke us into crafting Frankenstein monsters of half the nation. We simply stitch the latest evil trait onto the effigy and drag it into the public square to be burned, except instead of pitchforks and torches we do it all digitally so we don’t have to look them in the eye. We then act shocked when those we portray and attack of monsters begin to start acting like them.

We must resist the subtle seduction to reduce our neighbors to low-resolution caricatures, rather than relearn the art of living well together freely under a shared framework. We need to relearn the art of disagree well, which is the transformation of damaging conflict into healthy disagreement. We are a made to live together. We are designed to be dependent on each other rather than independent people, communities, races, and nations. The myth of the greatness of independence may be one of the most damaging things to the fabric of our world in the last three hundred years.

I believe most people want to do what is right. We want to be on the “right side” of history. When we went into the Czech Republic we were talking to our guide about this. He said his grandmother use to say, “The path to hell is full of good acts.” We said the version we grew up with, “The road to hell is paved with good intentions.” We need to realize and confess when we’ve done wrong, but I do believe move people want to do what is good and right. But even with that intention, we acquiesce to wrongdoings, small and large, out of self-preservation, the threat of lost opportunity or prestige, moral superiority, or simply a desire to be left alone.

This causes us to be split down the middle of ourselves. The Biblical writers Mark and James call it the disease of double-mindedness. What happens next, reminiscent of the logic of Adolf Eichmann who was one of the major architects of the Holocaust, is that average people, whether a police officer, a schoolteacher, an artist, a CEO—will excuse themselves by stating that they were “just following orders,” in hopes that the Machine will not grind them in its gears. They may even come to like the Machine. They may even come to operate it.

We mustn’t deceive ourselves into a perverse form of American, or Western, exceptionalism, thinking ourselves incapable of this irresistible aspect of human nature—the desire to suppress the “other.” It’s in all of us and in all of history from the conflicts of Northern Ireland, British Imperialism, South African Apartheid, American slavery and Jim Crow laws, German Nuremberg laws, and so much more.

We mustn’t excuse our own pet atrocities just because we believe the outcome is morally justified. A free society is messy, always poised on the edge of decay. Perhaps you’ve felt it was closer to the edge these last few years. But like a house, it must be maintained (as Courtney reminds me often that just because I vacuumed last week doesn’t mean I don’t need to do it again this week) by constantly revisiting and renewing our commitment to each other’s freedoms, especially the freedom to speak and think, to create—yes, even to fail.

Why did Cain kill his brother Abel? Because Cain bitterly resented his brother for possessing what he lacked. Cain feared Abel would be better and more loved and that he would be forgotten and left behind. Once that fear worked its way into Cain’s heart and mind, he could only see his brother as standing in the way of what he thought he deserved. That kind of deep resentment is woefully natural for human beings, as many mass movements can attest. We always are trying to identify who is coming to take what we have or what we believe we deserve. Perhaps that’s the saddest, but most played, song in history. That is why, in addition to refusing to live by lies, resentment and offense must be actively resisted by each one of us every day or we will begin to create enemies: those who live just on the other side of our empathy.

Well, that was a lot. Kudos to you if you read all that. Welcome to what goes on in my head on a nightly basis. So how do I conclude this reflection, and this trip?

I think I leave Germany with a renewed conviction to hear and sing the sad songs, but to sing the happy ones, too. I want to amplify them, because we can learn from the sad songs as well as the happy ones. We can, and must, learn from our mistakes as well as our triumphs. It’s okay not to have a perfect narrative. I know we try to cultivate one on social media with filters and selective posts and pictures, but I do not have a perfect story. No one does, so our nation and our church doesn’t either. We must work together to sing the songs that didn’t, and never will, end well. Perhaps in doing so we can work together to write a new song, a better song, that will be the happy song we will want to sing again and again.

Travel Notes from Pastor Stephen: Out of the Ashes

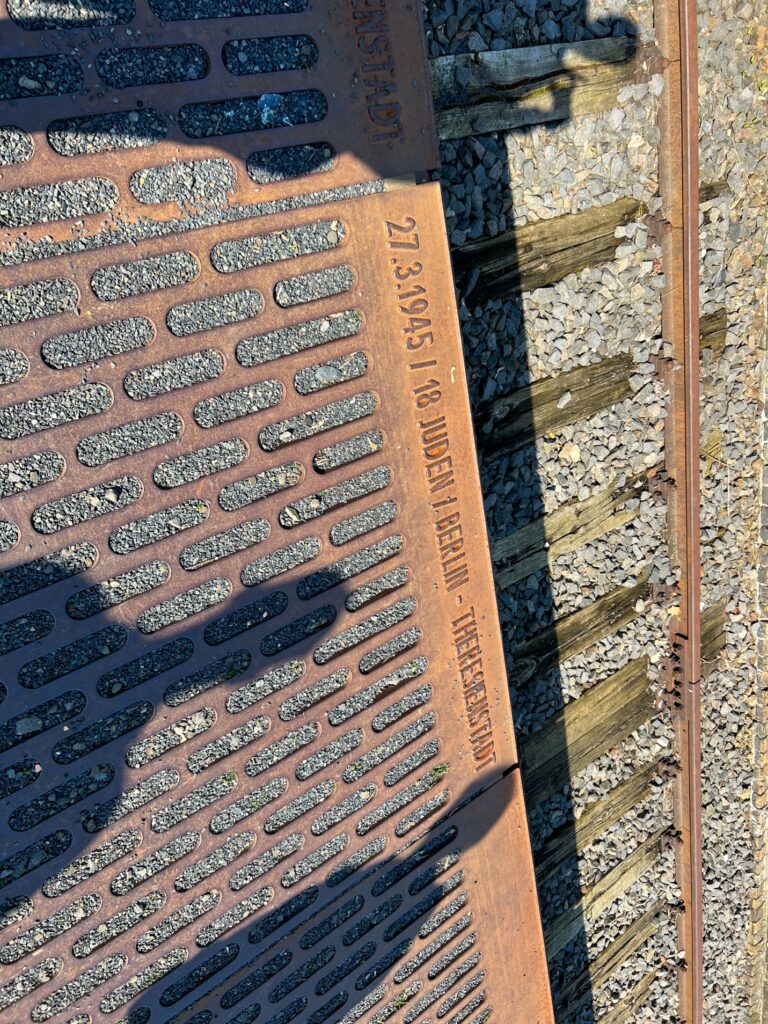

April 21, 2023Today we visited the city of Potsdam, the capital of the state of Brandenburg. On the way we visited the Platform 17 Memorial at Grunewald Station, where thousands of Jewish men, women, and children were deported from Berlin to various ghettos and camps across Germany and Poland.

The station, in the sparsely populated outskirts of the city, was chosen so the deportations would not be so visible and there was a less likely chance of public protest and outcry. The first deportation train departed from Platform 17 on October 18, 1941 with 1251 Jews sent to Lodz (a Polish Ghetto) and the last train was sent on March 27, 1945 with 18 Jews sent to Theresienstadt (a ghetto in what is now the Czech Republic). By the end of World War II, more than 50,000 members of the German Jewish population from the Berlin area were deported from this track.

The platform and tracks were abandoned after the war, but in the mid 1990s the Deutsche Bahn AG (German Railroad) were going to convert the old track to a train cleaning station. There was however outcry from the German public about this which forced the Deutsche Bahn AG to confront its own hard history and came to the following realization, which can be found on their website:

Research literature on the role of Deutsche Reichsbahn during the National Socialist regime comes to a unanimous conclusion: without the railway, and in particular without Deutsche Reichsbahn, the deportation of the European Jews to the extermination camps would not have been possible. For many years, both the Bundesbahn in West Germany and the Reichsbahn in East Germany were unwilling to take a critical look at the role played by Deutsche Reichsbahn in the Nazi crimes against humanity. In 1985, the year that celebrated that 150th anniversary of the railway in Germany, the management boards of the railways in both West and East Germany still found it difficult to even mention this chapter of railway history. Neither of the two German states had a central memorial to the victims of the deportations by the Reichsbahn.

This became painfully clear when the reunified railways were merged to form Deutsche Bahn AG. No business company can whitewash its history or choose which events in its past it wishes to remember. To keep the memory of the victims of National Socialism alive, the management board decided to erect one central memorial at Grunewald station on behalf of Deutsche Bahn AG, commemorating the deportation transports handled by Deutsche Reichsbahn during the years of the Nazi regime.

Would the railroad company have come to the conclusion without significant pushback from the public? Probably not. That’s often the case in corporate America, too, but the public can make a difference and force companies and other organizations to take an honest and critical audit of their own histories and determine if reparations, repair, apologies, etc need to be made.

Recently, Princeton Seminary did this after pressure from students and alumni. The Seminary published the results of its historical audit and its role in slavery. If you’re interested to read what they concluded and the actions they decided to take in response, you can read about it here.

Our voices do make a difference. Sometimes the squeaky wheel gets the grease and the persistent voice effects change. Jesus even tells a parable with this lesson (Luke 18:1-8).

The memorial on the platform contains 186 steel plates, each contains the date of transport, point of departure, destination, and the number of deportees. There is a concrete monument by Polish sculptor Karol Broniatowski that displays silhouettes of the victims being marched to the track that was unveiled in 1991.

But the most interesting and hopeful piece of the memorial for me is the one most often overlooked. We wouldn’t have even known about it without our guide. He pointed out a small grove of birch trees in front of the station. In November 2011, the Polish artist Lukasz Surowiec brought 320 birches from the area around the former concentration camp Auschwitz-Birkenau to Berlin, to ‘work against forgetting’. The trees are spread over the whole city, including this small stand outside Grunewald station. What grew out of the very ash of thousands of Jews was finally brought back, replanted, in Berlin. Out of the ash came life and return. The trees and the memories live on. The story lives on, and stories can be one of our most important legacies.

Out of the ashes was a bit of a theme today since we visited Potsdam. We crossed into Potsdam over the Glienicke Bridge, often referred to as the “Bridge of Spies.” The bridge straddled the border between East and West Berlin and, right in the middle of the bridge, a white border line was drawn. Due to its isolated location, the bridge was used to exchange high-ranking spies. The first exchange took place on 10 February 1962. The Soviet spy, Colonel Rudolf Abel, was exchanged for U.S. spy-plane pilot, Francis Gary Powers, shot down in the USSR in his U2 spy plane in 1960.

In Potsdam, we visited Sansoucci (without worry in French), a palace built by Frederick the Great as his summer residence. Frederick the Great was King of Prussia who grew and effectively used the large and advanced Prussian Army to expand Prussian territory and defeat France, Russia, and Austria in the Seven Years war. After the Seven Years War he built the Neues Palace as a giant guest house to show off that he still had money after the war.

Frederick is a rather interesting monarch and person. If you’re interested in history I suggest you read more about him. One of the things I learned was that Frederick is largely responsible for introducing the potato as a staple food in Europe. People pilgrimage to his grave to leave potatoes on it.

Potsdam was in East Germany after the war because of the agreement made between British US, and Russian leaders at the Potsdam Conference (more on that later). Potsdam fell into disrepair because the Soviet Union saw the Prussians as the precursor to what became the National Socialists (or Nazis). Therefore, they didn’t want to take care of the gardens of palaces of the Prussian kings.

In preparation for 1994, the thousand-year anniversary of the town, a lot of money was spent to restore the palaces and gardens of Potsdam. Out of the ashes of the destruction of the war and the ruins of the communist regime, Potsdam has been rebuilt to tell the story of Frederick the Great and others.

We can’t ignore our history. We can’t bury it and pretend it didn’t happen. We can’t ignore the inconvenient and hard parts. It’s all part of our story. We can learn from it and sometimes be thankful for how far we’ve come, how we’ve gotten better, and be thankful for the good that did come from those times. For example, an argument can be made that Fredrick the Great’s Seven Years War paved the way for American Independence because it cost England so much that it didn’t have the time, money, or energy to later invest in a war in America. Also, I like potatoes, so thank you, Frederick. But Frederick was by no means perfect. People suffered because of him and people found success, glory, and better lives because of him.

History is a mixed bag. It’s a teacher if we let it and it’s a part of our story. To truly know ourselves, we must know it.

The last palace we visited in Potsdam was Cecilienhof Palace, built in the Tudor style of an English country house from 1913 to 1917. Kaiser Wilhelm II had the residence built for his eldest son, Crown Prince Wilhelm. Until 1945 it was the residence of the last German crown prince couple Wilhelm and Cecilie of Prussia, but the palace is most famous for the conference held there from July 17 to August 2, 1945, in which the leaders of the US, Soviet Union, and Great Britain met principally to determine the borders of post-war Europe and deal with other outstanding problems.

Despite many disagreements, the three powers found compromises in the wake of war. It was decided that Germany would be occupied by the Americans, British, French and Soviets. It would also be de-militarized and disarmed. The country was to be purged of Nazi leadership and the Nazi racial laws were repealed. Germany was to be run by an Allied Control Commission made up of the four occupying powers.

Stalin was most determined to obtain enormous economic reparations from Germany as compensation for the destruction wrought in the Soviet Union as a result of Hitler’s invasion.

Truman and his Secretary of State James Byrnes insisted that reparations should be exacted by the occupying powers only from their own occupation zone. This was because the Americans wanted to avoid a repetition of what happened after the 1919 Treaty of Versailles. Then, it was claimed, the harsh reparations imposed by the Treaty on a vanquished Germany had caused economic crises which in turn had paved the way for the rise of Hitler.

The biggest stumbling blocks at Potsdam were the post-war fate of Poland, the revision of its frontiers and those of Germany, and the expulsion of many millions of ethnic Germans from Eastern Europe. In exchange for its territory lost to the Soviet Union, Poland was to be compensated in the west by large areas of Germany up to the Oder-Neisse Line – the border along the Rivers Oder and Neisse.

Through this process around 20 million people lost their homeland. The Poles, and also the Czechs and Hungarians, had begun to expel their German minorities and both the Americans and British were extremely worried that a mass influx of Germans into their respective zones would de-stabilize them. A request was made to Poland, Czechoslovakia and Hungary that the expulsions be temporarily suspended and when resumed should be ‘effected in an orderly and humane manner’.

About 14 million Germans lost their homeland. Within a short period of time, they had to be absorbed into the four zones of occupation in Germany. The arrival of forcefully expelled persons created a volatile situation. About one in three Germans lived in emergency shelters for years after the war ended.

The Potsdam Conference fundamentally changed the landscape of Europe. Out of the ashes of war it tried to build something new and stable that would allow for peace. It certainly wasn’t perfect. It’s easy to critique the decisions made, especially with the luxury of hindsight. It paved the way for the Iron Curtain and years of communist oppression for what are now eastern European nations. It dislocated millions and changed borders. There couldn’t have been a perfect answer to all the postwar questions especially with the competing interests of Britain, America, and the Soviet Union.

Sometimes the best we can do is the best we can do. We cannot let the perfect become the enemy of the good. We can learn from mistakes and try to do better, but sometimes all we have are bad and difficult choices and options. We need to be able to offer grace as well as critique to our histories. If ridicule, shame, judgment and guilt is all we walk away with after studying history, then we are studying it wrong. Sadly, that’s how it is often presented. We need to reckon with the wrong, but we need to celebrate the good, too. And we need to recognize that perfect solutions rarely exist.

We also need to remember that rebuilding takes time. Of course, that’s easy to say if we aren’t the ones suffering during that waiting period, but it’s a reality nonetheless. Progress is often in steps. We don’t make one giant leap to the end. We’ve come a long way since WWII. Germany has come a long way, and many of the former communist nations like the Czech Republic (formerly part of Czechoslovakia) have come a long way economically and politically. It’s been a long road, but progress has been made. I think we can celebrate that even if it wasn’t immediate and even if the journey was fraught with pain and suffering. Rebuilding and new life takes time.

This is true of our Christian journey as well. While God’s grace and love is always for us, we don’t immediately turn into the disciples God wants us to be. It’s a life-long journey. We make mistakes and we experience successes. We confess often, we don’t pretend we have no sin. We do not deceive ourselves. But we also should celebrate our growth as children of God. A religion built only on guilt does not lead to life.

My favorite part of today was having dinner with Susan Neiman. It was a riveting conversation that has left me with a lot to think about. She talked about how she’d write her book differently today and new projects she’s thinking about. We talked about how history is taught and how we cannot make guilt the one and only outcome of our reckoning with history. We have to have hope and we have to highlight the heroes, too. I hope I’ll have more time to share some of that conversation with you after I’ve had more time to process it. I am looking forward to reading her newest book soon, and she recommended some interesting looking books as well. It was a valuable conversation that has helped me think more about what is required for peace and reconciliation in our world.

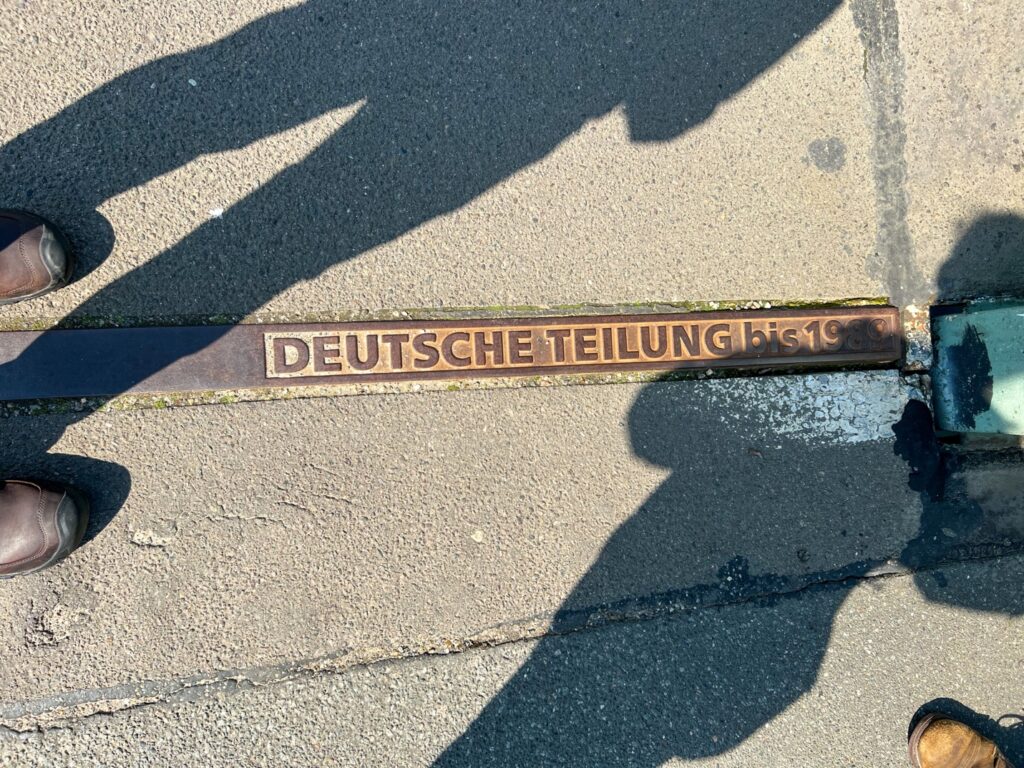

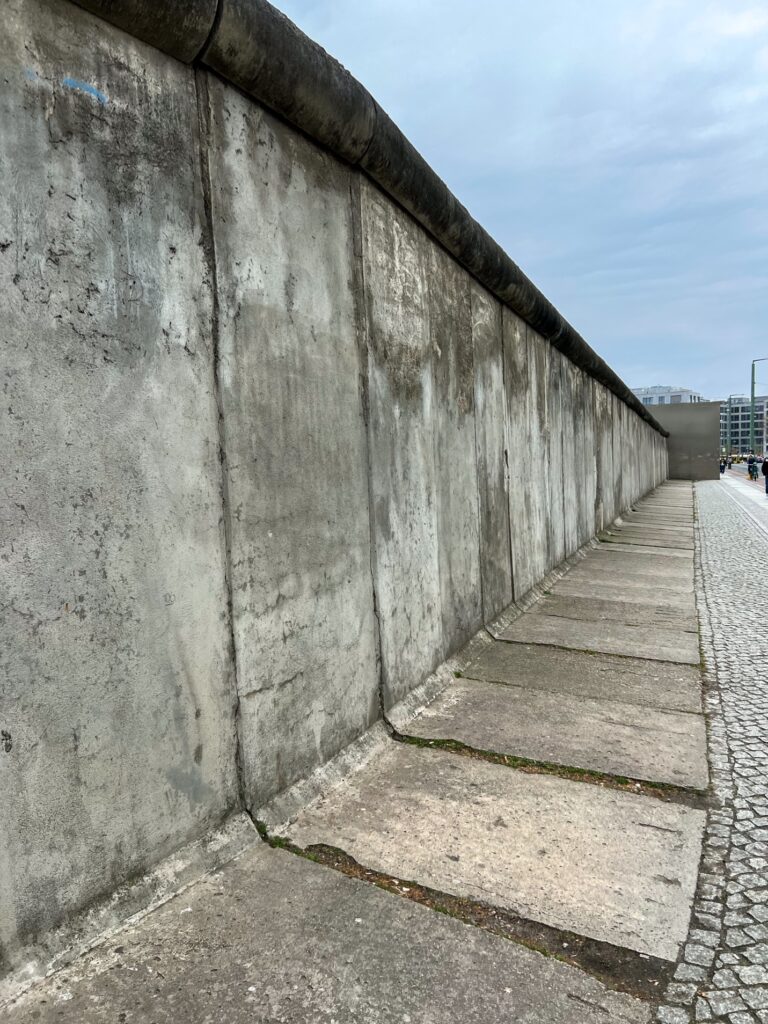

Travel Notes from Pastor Stephen: And the Walls Came Tumbling Down

April 20, 2023Courtney and I had the opportunity to visit some of the remnants of the Berlin Wall and the official Berlin Wall memorial over the last couple days. For a long time, the wall was the city’s premier tourist destination and perhaps Berlin’s most famous structure. While the wall is gone, its ghost remains in the form of rubble, souvenir pieces that are scattered throughout the world, and a few places where the remnants remain to remind Berlin and the world of what Germany was, is, and still can be.

An agreement made by the victorious Allied forces of WWII at the Potsdam Conference of 1945 carved Berlin into sectors controlled by each nation. Part of the agreement was that military forces could move freely between the sectors.

In subsequent years, Berlin became a strategically important Cold War bargaining chip – the European ground zero of the conflict between East and West.

The western sectors became the “shop front window of the western world.” Residents were paid extra for living in the shadow of the Soviet Union and were exempt from required military service.

In the Eastern sector of the city, the East German government brought law and order — and fear — to the population. The Soviet Union sought to establish a Soviet satellite representing the aims and interests of Moscow. The Stasi, or secret police, was one of the largest spy networks in the world. There was one Stasi agent for every 68 residents in East Berlin. But East Germany also wanted to show the world the benefits of the Communist State, so they embarked on some ambitious building projects like the TV Tower in Alexanderplatz.

You can see the remnants of the wall everywhere in Berlin. Even where the wall is gone, there are special bricks along roads and sidewalks that mark where it once stood. It still carves up the city: the different districts still each have a unique character.

Wim Wenders, in 1987 wrote, “For me visits to [Berlin] over the past 20 years have been the only genuine experiences of Germany. History is still physically and emotionally present here… Berlin is divided just like our world, our time, and each of our experiences.”

Our world, our nation, our communities and even churches are divided. Our lives are divided between obligations, desires, jobs, and families. What gives me hope is that the wall came down, not through military might, or governmental pressure, but through the persistent will of the people. We can overcome.

We learned stories of people building tunnels under the wall to help friends and family escape East Germany. We saw pictures of people who jumped out of buildings when the wall first went up and an East German police officer, Conrad Schumann, who jumped the barbed wire. Often those stories didn’t have happy endings, and the family they left behind were punished by the East German authorities or they themselves were psychologically tortured even while in West Germany by having to live with constant fear and intimidation from the Stasi. For example, they’d send agents to just break into someone’s house and move things around. Conrad Schumann, the man who jumped the wire, died by suicide shortly after the wall came down.

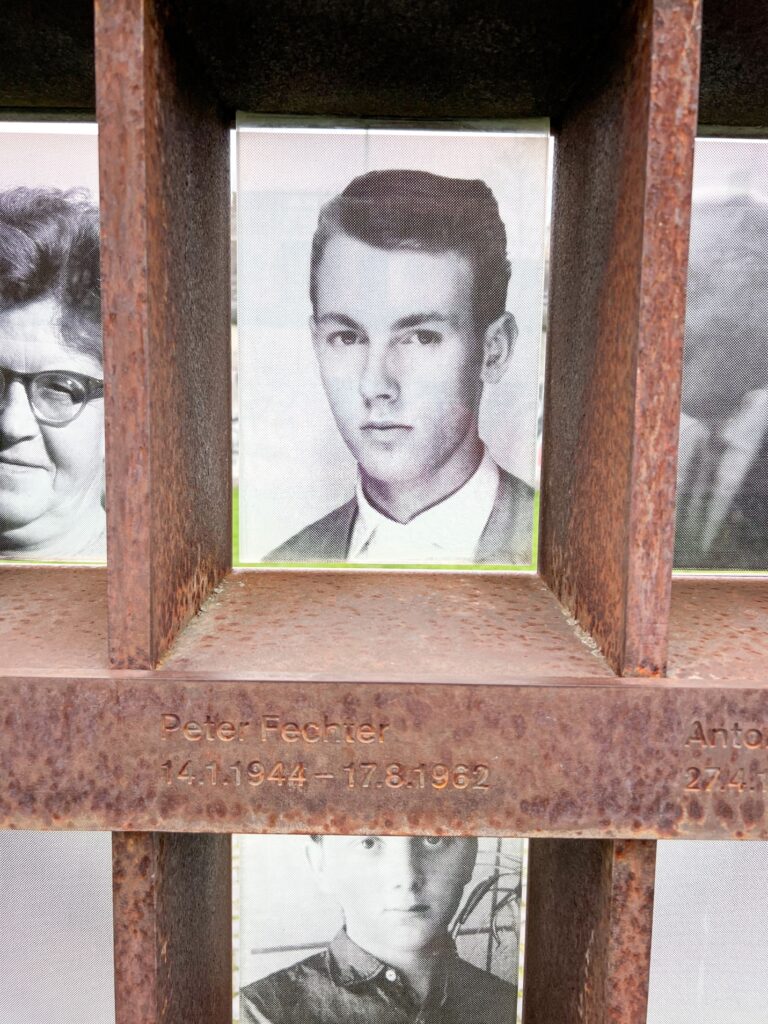

We visited the one place where the full wall remains, which includes a watchtower and two walls with the death strip in between. There were even places where a third wall stood. As Courtney said, “It’s more the Berlin Walls than the Berlin Wall.” East Germany made it really hard to escape. At least 140 people died trying to cross the wall, but that doesn’t count those killed before they made it to the wall, or those who died after crossing. We saw a memorial to all 140 with their names and pictures. Courtney remembers her dad sharing the story of Peter Fechter, an 18-year-old boy, who was killed trying to cross the wall in 1962. He remembered seeing it on the news when he was a young boy. Perhaps you remember seeing the video footage, too.

The wall was a defining thing for Berlin and for Germany. I still remember learning in school about both East and West Germany. I also remember when the wall came down.

I shared the story of Lutheran pastor Christian Führer last fall in a sermon. He believed that the wall that divided East from West was evil and that human freedom was not just a political issue but also a theological issue. So, he began hosting weekly prayer services for peace.

The gatherings at the church were small at first, but once word spread, the crowds grew to the tens of thousands. And then, in October 1989, the Monday-night prayer service culminated in a standoff between this peaceful resistance and the powerful Communist Party. The pastor admonished the demonstrators to be nonviolent. “Put down your rocks,” he preached. So the demonstrators carried candles instead.

And when the Communist Ministry for State Security arranged to occupy more than 500 seats in the church during the Monday prayer service, more than 70,000 peaceful citizens gathered in the streets. Meanwhile, heavily armed security officials waited for instructions from Moscow and Berlin on when they could subdue the demonstrators. They were ready to exercise their power and control. But the order never came, and the police gave up.

The security chief who desperately wanted to subdue the rebellion by force was later shown on film as he stared out at the crowd in front of his headquarters—the crowd whose freedom march had begun in the church, the crowd who had heard the prophetic witness of a pastor emerging from decades of oppression saying, “Let’s move forward in peace,” the crowd so enormous that it stirred fear in the incredibly powerful chief of security, with his tanks and tear gas and firearms. And yet, in that potentially explosive moment, the security chief ready to unleash his armed guards was found saying, “We planned for everything. . . . We were prepared for everything, everything—except candles and prayer.”

The Berlin Wall came down less than a month later. There are other stories like these that speak to the persistence of hope and peace in the human spirit. Stories of people who were able to cross the wall and those who continued to protest and push for its removal. It’s easy to let the human capacity for evil dominate our thinking, but we would do well to remember that the wall came tumbling down.

I learned the story of Harald Jaeger who, for many Germans, is the man who opened the wall because he defied his superiors’ orders and let thousands of East Berliners pour across his checkpoint into the West. He said he didn’t really open the wall, it was the people who stood there who did it. The will of the people was so great, he had no alternative.

It remains me of a quote by Carrie Chapman Catt who was a suffragette: “When a just cause reaches its flood-tide… whatever stands in the way must fall before its overwhelming power.”

Those people had come to his crossing at Bornholmer Street after hearing Politburo member Guenther Schabowski mistakenly say at an evening news conference that East Germans would be allowed to cross into West Germany. For East Berliners longing to go to a part of their city that had been off-limits for 28 years, this was welcome news. Schabowski was a member of the ruling party, so it was assumed that what he said was law.

But Jaeger had always been told that the Berlin wall was a “rampart against fascism.” He cheered when it went up. As a communist who served in the army, he was doing his duty and was fighting the good fight against the bad guys. How often do we think we’re doing the right thing because of what we’ve been taught and how we’ve been raised, only to find out it was never so clear cut? Do soldiers ever think they are “the baddies”?

At first, between 10 and 20 people showed up at Jaeger’s crossing right after Schabowski’s news conference. They were waiting for some indication from Jaeger and the guards that it was okay to cross, but none was given. It wasn’t long before crowd grew to 10,000 shouting: “Open the gate!”

Jeager’s orders were to send the people away, but he knew that was unlikely. He had only ever had to fire one warning shot in the 25 years he worked at the wall, but he worried the crowd could grow unruly and people would get hurt, even if it wasn’t from guns.

To ease the tension, he was ordered to let some of the rowdier people through, but to stamp their passports in a way that rendered them invalid if they tried to return home.

But this only fired up the crowd more. They could see freedom and a better day: it was so close. Despite orders from his higher ups, Jaeger eventually ordered his guards to allow all East Berliners to travel through.

He estimates that more than 20,000 East Berliners on foot and by car crossed into the West at Bornholmer Street. Some curious West Berliners even entered the east.

People crossing hugged and kissed the border guards and handed them bottles of sparkling wine, Jaeger recalls. Several wedding parties from East Berlin moved their celebrations across the border, and a couple of brides even handed the guards their wedding bouquets. I imagine it looked a bit like the scene forever immortalized in the picture from Times Square on VJ Day in 1945. There is such ecstatic spontaneous and generous joy when peace breaks out.

What I’ve found about stories of peace throughout the world is that it’s often the everyday people who play critical roles, and the masses. Peace doesn’t happen because of a few political leaders, though they certainly have a role to play. Peace and reconciliation happen when the people not only desire it: they demand it and work for it with humility and grace.

The wall is gone. Only a few remnants remain to remind the world of Berlin’s past hardship and triumphal reunification. I’m glad there are places like the Berlin Wall Memorial to visit because they aren’t just reminders of a divisive and scary Cold War. These places remind us there is hope. We can reunite after divisions: physical, ideological, theological and legal. Peace can break out at any moment. We can find one another again.

It’s Time for the PW Birthday Offering

April 19, 2023The Birthday Offering of Presbyterian Women celebrates our history of generous giving. Launched in 1922, the Birthday Offering has become an annual tradition. Over the last century it has funded over 200 major mission projects that continue to impact people in the United States and around the world. While projects and donation amounts have changed over the years, Presbyterian Women’s commitment to improving the lives of women and children has not changed. For 2023 there are two projects:

- In Tallahassee, Florida, Making Miracles Group Home has been helping young mothers break the cycle of poverty and homelessness due to abusive relationships, addiction, incarceration and early motherhood. Currently women with older children or multiple children cannot be served. The Birthday Offering grant will fund a second group home for five more families.

- The Berhane Yesus Elementary School in Dembi Dollo, Ethiopia added a kindergarten in 2012, but the class has outgrown meeting in the chapel. Land has been donated and the grant from the Birthday Offering will fund the construction of a kindergarten space for this school serving grades K-8.

In coming weeks, you can read more detailed information about these projects in the eNews. Your continued support this year will allow PW to fund next year’s projects. You can give online, deposit checks in the offering boxes, or mail checks to the church. Please notate checks “PW Birthday Offering.” Together let us lovingly plant and tend seeds of promise so that programs and ministries can grow and flourish.

Travel Notes from Pastor Stephen: Sachsenhausen

April 19, 2023Content Warning: Today’s reflection includes some disturbing details about what happened at a concentration camp near Berlin.

Today I had the sobering experience of visiting Sachsenhausen Concentration Camp. It was a profound experience, made more so by our visit to the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe yesterday and my own visit to the Yad Vashem (the Holocaust Museum in Jerusalem) several years ago. It’s a place no one particularly wants to go (for enjoyment) but should go. Our guide shared his own mixed feelings with taking so many people there; he had a sense of fulfillment and purpose in sharing what he knew with others, but it is also a part of that hard history that can weigh on you.

I have studied the Holocaust in various ways (courses in college, reading in seminary, my own curiosity), but seeing it up close was a new experience. It put flesh and bone, brick and mortar to the horror, and I learned small details and stories you don’t get from courses and books. Courtney can share a lot more about this, but it’s a bit like slavery in the US. Most people know a bit about it and a few bad things and stories, but unless you really study it and go to the places where it happened and talk to the experts there, you don’t really know how horrible it really was. I think the Holocaust is similar. You can read and watch programs, but the deeper you go, the more horrors and atrocities and derangement you will discover.

The SS established the Sachsenhausen concentration camp as the principal concentration camp for the Berlin area. Located near Oranienburg, north of Berlin, the Sachsenhausen camp opened on July 12, 1936, when the SA (brown shirts) transferred 50 prisoners from another camp to begin construction of Sachsenhausen. By the end of 1936, the camp held 1,600 prisoners, who were mostly political prisoners. The camp at its peak held over 50,000 prisoners ranging from communists, prisoners of war, homosexuals, ethnic groups such as the Roma and Sinti people, and Jews. Prisoners of Sachsenhausen included Pastor Martin Niemöller, former Austrian chancellor Kurt von Schuschnigg, and Joseph Stalin’s son, Yakov Dzhugashvili.

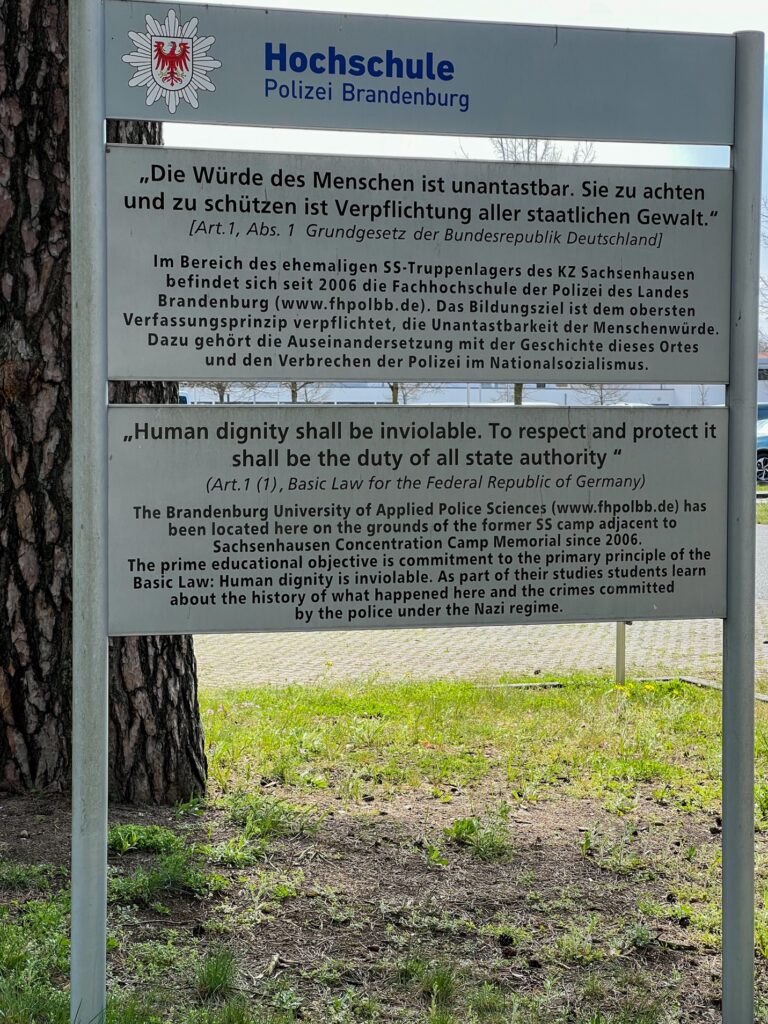

Before you enter the actual concentration camp gates, you pass a few buildings on the other side of the street. These two massive, unattractive, military style buildings were used to train SS guards. Today, they are used to train the local police force. This is Germany’s way of continually reminding its people, especially those gaining a certain amount of power, of the dangers that come with that power and a warning not to repeat history. I find it incredibly wise, insightful, and courageous to train those who will gain power in the shadow of the atrocities power can do. There’s a sign you can see near the buildings from the path in Sachsenhausen with the first article of the German Constitution and a reminder of why police are trained there.

Until around 1990 it was required of every German student to visit a concentration camp. It is no longer required, but it is rare for a student not to visit one. I never went to a place with a hard history on a field trip, but there were plenty nearby I could have gone to. Luckily, I had parents who took the time to take me to places where I could learn the history of our country: the good, the bad, and the ugly.

We too often want to hide from our history instead of letting it challenge us, convict us, convert us, and maybe even ultimately redeem us. We don’t want it shoved in our faces, but Germany puts it right there for all to see: not just students, not just tourists, but those who would have power and responsibility.

After arriving at the actual camp, our first stop was Tower A, or the entrance of the camp grounds. This structure is the only entrance and exit that Sachsenhausen has. It’s a rather typical-looking entrance, resembling the famous picture of Auschwitz not only in structure, but also in history: over 200,000 prisoners were registered in front of and passed through it. A much smaller number was able to come out, some dying of malnutrition, others of cold, and some through suicide by throwing themselves at the electrical fence, but Sachsenhausen was not an “extermination camp” like Treblinka and Auschwitz.

While the entrance might have looked typical, the camp is very different from other camps. For one, Sachsenhausen was built in the shape of an equilateral triangle, with its roll-call area (where the prisoners were counted every morning and evening) directly in the center. It was modeled after a Panoptical – the ideal prison, where the prisoners felt exposed to the eye of the guard at all times. It was, in the words of Heinrich Himmler, the prototype of the “modern, up-to-date, ideal and easily expandable concentration camp” (1937), the ultimate symbol of Nazi oppression and terror. Machine guns on top of Tower A could easily see and shoot everywhere a prisoner could be or go.

Today, little remains of the original landscape of the camp: just a few buildings. The outline of many more are laid out in iron and stone. It’s much more open now, allowing visitors to see the camp from end to end and wonder, how it is possible for a camp designed for 3,000 people to house as many as 58,000 people at one time at its peak?

Unlike places such as Auschwitz, the buildings at Sachsenhausen have mostly disappeared. A few originals remain and a few have been rebuilt. According to German law they can only be rebuilt using original material. The emptiness of the camp gives it a chilling effect, but what it lacks is the feeling of overcrowdedness which certainly existed when the Nazis used it to hold at least six times the number of people it was originally intended for.

One of the barracks has been reconstructed and turned into a Jewish Museum. We saw the small room where hundreds would be kept, three to a bunk.

In 1992 neo-Nazis broke into the camp and attempted to burn the museum down. They were unsuccessful in destroying the building but did cause damage. The building was not redone; instead, the damaged and charred ceiling and was left as a reminder that persecution and hatred is not entirely a thing of the past, but rather an attitude which still is with us today.

Once again, I think we can learn from Germans. They refuse to whitewash the sins of yesterday and today. Yes, there are those who may think Anti-Semitism is a thing of the past in Germany, but choices like this one force us to confront the truth that it is not. I understand cleaning the graffiti of Nazi symbolism off memorials in the US, but what if we left it there so we would have to reckon with the Anti-Semitic reality that is so real and constant for so many of our neighbors? What if we stopped fixing what hate attempts to deface and destroy and instead shine light on the hate that still persists and pervades everything in the hope that hate will write its own obituary? I certainly understand why we wouldn’t want some hateful graffiti on monuments; it can trigger people, it gives it a spotlight, etc. But I can also see where in some instances it might be wise not to just repair what hate tries to destroy.

Over the course of our time at Sachsenhausen we learned about the camp, its guards and leaders, and its prisoners. There are eerie and disturbing pictures of guards and commandants looking positively gleeful and nonchalant as they observe the abject suffering right in front of them, sometimes even kneeling right at their feet.

We saw original artifacts used to torture and punish prisoners. It’s not some far off historical idea: it’s right in front of you, staring you in the face. This happened to men who were probably not much different than me. It reminds me I don’t have to look in my own country to find this sort of horror, whether it’s slavery, treatment of indigenous people, or things that happen in our own industrial prison system. Some of the pictures at Sachsenhausen reminded me of the pictures I saw of guards in US military uniforms at Abu Ghraib prison.

The number of Jewish prisoners in Sachsenhausen varied over the course of the camp’s existence, but ranged from 21 at the beginning of 1937 to 11,100 at the beginning of 1945. Many of the earliest Jewish prisoners were there because of political views and not race. Almost 6,000 Jews arrived in Sachsenhausen in the days following the Kristallnacht (Night of Broken Glass) riots. Many of those prisoners were released in exchange for their promise to emigrate (at their own expense).

There was a marked increase in the number of Jewish prisoners when, in mid-September 1939, shortly after World War II began, German authorities arrested Jews holding Polish citizenship and stateless Jews, most of whom were living in the greater Berlin area, and incarcerated them in Sachsenhausen. Thereafter, the number of Jewish prisoners decreased again, as SS authorities deported them from Sachsenhausen to other concentration camps in occupied Poland, most often Auschwitz, in an effort to make the so-called German Reich “free of Jews” (judenfrei).

In the spring of 1944, SS authorities began to bring thousands of Hungarian and Polish Jews from ghettos and other camps to Sachsenhausen as the need for forced laborers in Sachsenhausen and its subcamps increased. Many of these new Jewish prisoners were women. By the beginning of 1945 the number of Jewish prisoners had risen to 11,100.

Sachsenhausen wasn’t only a prison; it was a business. Prisoners were used as laborers to make bricks for building projects in Berlin and eventually to remove unexploded bombs in Berlin during the war. We learned that shoe companies tested their shoes, especially hiking boots, at Sachsenhausen. There is a semi-circular stone track in the main courtyard where often prisoners of war (who were in better shape) would be forced to walk mile after mile back and forth with heavy packs to test the soles of boots.

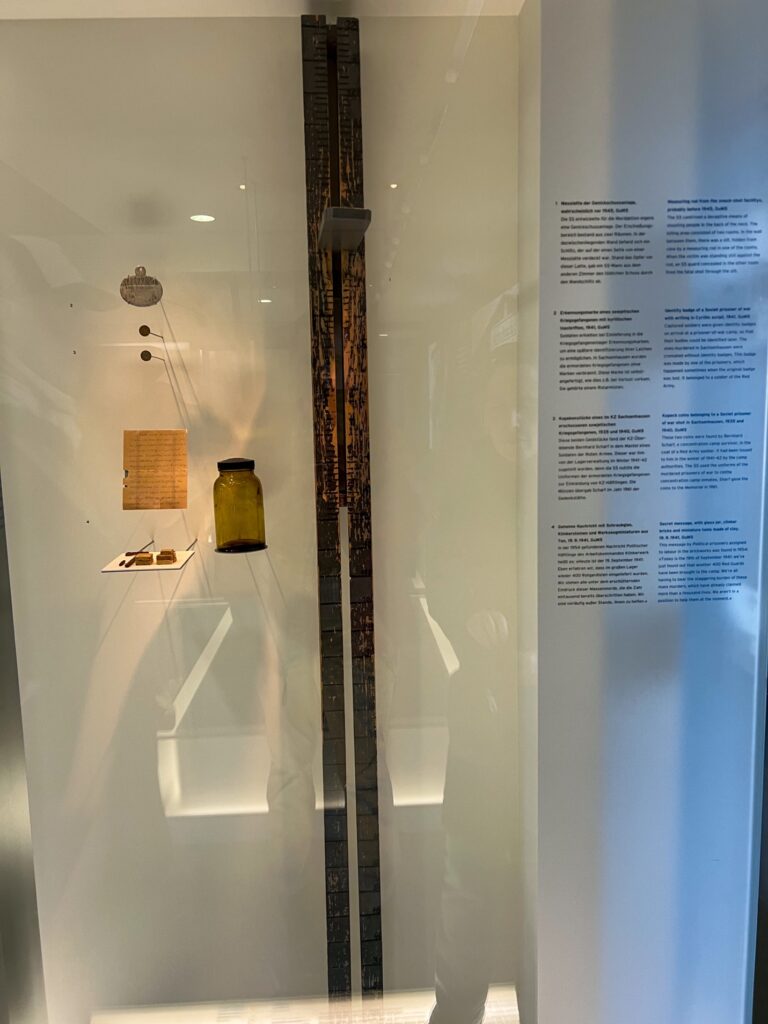

The first group of Soviet prisoners of war arrived in Sachsenhausen at the end of August 1941. By the end of October 1941, the SS had deported about 12,000 Soviet prisoners of war to Sachsenhausen. Camp authorities shot thousands of Soviet POWs shortly after they arrived in the camp through an elaborate ruse. The Soviets would be taken into what looked like a medical facility and greeted by men in white coats and aprons they assumed to be doctors. Their height would be measured and they would be given a token and head to the next room where another “doctor” would check in their mouth. They were checking for gold teeth but the prisoners didn’t know. Then they’d go to another room that was more soundproof and had music playing. There they would stand against another height measuring stick (pictured below) but this time a guard in a hidden room would shoot the prisoner with a small caliber pistol in the back of the neck through the gap in the measuring stick. Other prisoners would then drag out the body to be taken to the nearby ovens. Estimates of Soviet POWs killed at Sachsenhausen range from 11,000-18,000.

There was a special prison within the camp for prisoners they didn’t want intermingling with other prisoners, or who they wanted to torture in other ways, or keep alive. One of those prisoners was Joseph Stalin’s son. They kept him alive in case he could be used, but when Hitler tried to exchange him for Field Marshal Paulus (he lost the battle of Stalingrad and Hitler wanted him so he could execute Paulus himself), Stalin said, “Why would I trade a Field Marshal for a Corporal?” Stalin’s son was dead shortly after, but it was staged to look like he was killed during an attempted escape.

Martin Niemöller, a Lutheran pastor, was also imprisoned at Sachsenhausen for eventually speaking out against the Nazis as part of the Confessing Church, but not before he initially voted Hitler into power. Niemöller later wrote that he “voted for Hitler because of the Nazi pledge to honor Christianity and to provide Germany with a strong leader who would restore German pride.”

Niemöller said,

“I had an audience with Hitler, as a representative of the Protestant Church, shortly before he became Chancellor, in 1932. Hitler promised me on his word of honor, to protect the church, and not to issue any anti-Church laws. He also agreed not to allow pogroms against the Jews…Hitler’s assurance satisfied me at the time. On the other hand, I hated the growing atheistic movement, which was fostered and promoted by the Social Democrats and the Communists. Their hostility toward the church made me pin my hopes on Hitler for a while. I am paying for that mistake now; and not me alone, but thousands of other persons like me.”

We sometimes forget that Hitler came to power legally. He didn’t lead a military coup. He was voted for by many Germans, but he couldn’t take full control yet because he didn’t have the votes. He actually made a deal with the Vatican and the Catholic church in Germany that got him the votes to suspend democracy and give him emergency powers. The church, Protestant and Catholic, was not just complicit in Nazi Germany, they were willing supporters.

Perhaps you’ve seen the pictures of German churches with Nazi flags on their chancels. This is one reason why pastors get so nervous about signs of nationalism in the church that are mixed into worship. It’s never been a good mix, and Nazi Germany is a not-so-distant memory of how bad it can go when the church and state get together. It’s never gone particularly well, but Nazism is by far the worst example.

After we saw the special prison, we made our way to Station Z. We saw where prisoners were executed by firing squad, which was the easiest and most dignified way to die in Sachsenhausen. The guards at Sachsenhausen had a joke that spread to all the camps: the only way out is through the chimneys.

After the firing squad area, we saw what was left, just the foundations of the killing rooms. Sachsenhausen wasn’t an extermination camp like Auschwitz, but it was a sort of testing and proving ground for the Holocaust. Many of the decisions made for camps like Auschwitz happened at Sachsenhausen.

For example, they had a small gas chamber at Sachsenhausen where they worked to perfect the most efficient way to exterminate prisoners. They learned through trial and error and that is what led to the larger gas chambers that looked like showers at camps like Auschwitz.

After prisoners were poisoned with gas their bodies were taken to the ovens. Next to the foundation of the gas chambers were the “medical offices” the Soviets were taken to. Without the walls, you can see how close these places were to the ovens used to reduce the bodies to ash for easier disposal.

I’m thankful for the opportunity I had today, but it wasn’t enjoyable. It was poignant and powerful and depressing and educational and sad and hard and necessary.

Susan Neiman has an interesting section in her book Learning From The Germans about these concentration camp memorials and a conversation with the director of the Buchenwald Memorial. The Memorial there goes to great lengths to show the residents of the area knew exactly what was happening and chose to do nothing from the beginning of the camp being built there until the very end. The exhibits at Buchenwald and Sachsenhausen don’t just memorialize the dead and proclaim the suffering that happened. These camps — now turned memorials and museums — ask the bigger questions about how what happened was justified, why there was so little resistance, and what ideologies and actions led to what the camps and their acceptance by the German people.

For example, the residents of the Weimar region didn’t want Buchenwald named for the wood it was in because that wood was made famous by Goethe. They knew enough to know that the camp would stain that legacy, but they didn’t care enough to stop its construction, just it being named for their beloved wood. We think through more than we want to admit. We play ignorant, but we rarely are as we play. We think in playing ignorant we can still be found pure and clean and guiltless. It was not true for the citizens of Weimar and it will not be true for us if we let injustice linger and thrive in our towns and country.

The people of the town around Sachsenhausen knew what was happening: the camp and community were in a symbiotic relationship. They knew, but it’s also not so simple as they knew and let it happen.

Our guide made the point that the real question isn’t, “would you have done something, but when would you have done something?” People thought it was temporary because it was before and by the time things get really bad there’s the question of who do you endanger by speaking up and what can be done when things are already so bad and so established. Sometimes things happen so fast, the window for effecting change is already closed.

Sometimes you may know something is wrong but just have no idea how to stop it. Perhaps you’ve felt or feel like that. I lament all the mass shootings in the US. I know it’s wrong but I don’t know how to stop it. I’m not sure what I can do. As I see rights and opportunities taken away from groups of people, I know its wrong but I’m not sure what I can do to stop it. I can use my voice, but I’m not always sure what good that will do except get half the church mad at me, and what good does that do? That doesn’t mean we should never act, we should never speak up. It’s often not simple. There is the question of not only if, but how, and when, and at what cost. Some people who had little responsibility had an easier time taking a stand than those who felt responsible for aging parents and children. It’s hard to risk your own life, but it’s much harder to risk the life of those you love. That element was certainly in play during the Nazi regime in Germany and when East Germany was largely run by the Stasi.

We can’t just play this game of “what would I have done if I lived next to Sachsenhausen in 1939 or 1944?” That doesn’t do us any real good. The director of the Buchenwald Memorial doesn’t want people to come and put themselves in the place of the prisoners or guards or the citizens of the surrounding towns. He doesn’t want people to consider what they would have done in 1942 or ’44. He says, “Our memories are narrowed by the Holocaust, which shields us from the history of its causes. The real question is ‘What would I have done in ’32 or ’33? Then it’s a question about courage, but not a matter of life and death. And it’s not one you can answer by saying there was no chance for effective resistance.”

As I said in an earlier reflection, we have to act when a movement is beginning — not when it has the inertia to keep moving despite the roadblocks put in its way. Often we don’t know that “when” until it’s too late. Some Jews left Germany early and others kept thinking things would get better. It’s a difficult decision. When do you risk your livelihood, the life you’ve known, everything because you’re afraid you won’t have a life otherwise? How long do you wait? What if you’re wrong and leave too early?

I imagine that’s something many of the refugees in this country can tell us more about. For the most part, no one leaves their home and becomes a refugee because they want to or think it will be easy. They usually have no choice and it’s the hardest decision they have to make. I can’t imagine that kind of decision, and therefore try to have empathy for anyone who feels they have to risk everything to flee. What can we learn about why people choose to flee their homes today? Instead of just looking at statistics and facts of who is coming and from where and what it means for the nations that receive them, can we try to investigate and understand why they made that choice? What evil is pushing them out, leading them to make such a dangerous and costly choice?

We need to think about the causes of evil and not just memorialize its effects. I think that’s how these Concentration Camp Memorials and museums like the Topography of Terror, which we saw yesterday, help us. We aren’t just remembering something bad happened, we’re discovering why and how it happened.

What would that mean and look like for museums in the US? To not just teach what happened on the Trail of Tears, but really dig into who did it and why, and how everyone else was perfectly fine with sending the Cherokee packing from lands they had lived on for generations. What would it look like in a museum about slavery in the US to really examine why we had slavery and why the whole nation, not just the South, was content with the institution for so long? I think we’d uncover some horrible truths, but also learn things weren’t as simple as we might believe.

Courtney can tell you a lot about how it was actually illegal for most southerners to free their enslaved persons. And while some could upon their deaths, it could leave their family bankrupt and worse. Courtney says time and time again that people often have far less choices than we assume they have. But we oversimplify and we don’t study the why and the how, we often just settle for the what. We name what happened and move on.

The common model for museums and memorials is to celebrate the triumphs and heroes and mourn and memorialize the victims. Germany is doing something new: they are asking the right questions about the perpetrators, their motives, and the social conditions around them. When we can understand the why, we are better equipped to not repeat our past shame and evil.

In studying how and why the Nazi plan worked so well in Germany, it all feels really similar to so much in the US, from slavery and Jim Crow to Nixon’s Southern Strategy. It’s all there in the same playbook. While they’re not the same, it starts in the same place, appealing to the same fears and desires, making the same kind of promises.

What can we learn from that? What does it tell us about ourselves and our leaders and how the masses will allow injustice against some even if it doesn’t really benefit them?

Read more Berlin travel notes:

- Why Berlin? (4/16/23)

- Learning from Germans (4/17/23)

- Ghosts of Berlin (4/18/23)